The Importance of Being Present in Resolving Conflicts and Disputes

By David Carden

Successful negotiations to resolve commercial and diplomatic disputes depend upon the ability of the parties, diplomats, mediators, advisors, and counsel, to correctly read both the situation and one another. Unfortunately, they often fail to do so, missing opportunities to reach a resolution. Sometimes what they miss relates to the ‘merits,’ justice, and the parties’ self-interests. But they also can miss opportunities to settle disputes based on considerations unrelated to these factors. Sometimes people are prepared to set self-interest, the desire for justice, and the merits aside. I have seen it happen many times.

It is commonly believed that the merits, the desire for justice, and self-interest govern the negotiations resolving diplomatic and commercial disputes. While these are powerful drivers, people can also look beyond a current dispute and find the benefits of resolving it based on other considerations. When they do, my observation has been that the parties are proud of what they have accomplished. Mediators and negotiators would be well-served to look for instances when the principals are interested in, and capable of, this approach. Here are some things that can be done to help make this possible.

Creating Safe Spaces to Allow Parties to Be Present

The first step is for diplomats and mediators to develop mechanisms to pull the parties away from their respective positions. These mechanisms will vary with the circumstances, but all require creating a safe space for the parties to admit their doubts, even if only to themselves, and abandon what they had considered certainties. Said another way, mediators and negotiators should do what they can to ensure the principals, alongside their advisors and counsel, are present. By this I mean that they are prepared to leave the past behind, and to listen and change.

One key to ensuring presence is to avoid theater and posturing. The honesty of all concerned is necessary to open avenues to real resolutions based on more than their perceived self-interest. But opening such avenues can be a real challenge, especially when parties fear being blamed for an outcome considered to be undesirable. Counsel and advisors contribute to this challenge by trying to impress their principals. Eliminating posturing can be difficult, as people often do so because they fear revealing too much, believing it is safer to proceed based on ‘truths’ grounded in past experience, unrealistic or misinformed expectations, history, emotion, shame, and economic self-interest. Too often they don’t listen and learn, but dissemble and defend. Sometimes, they also fear being second- guessed by superiors.

The approaches taken by diplomats and mediators can also do harm, especially when reliant upon their experiences in past cases without considering how the present case might differ. They can also be risk-averse , leading them to promote less than a full solution to the problem at hand. Agreeing to a ceasefire without doing the hard work to address the underlying causes of a conflict is an example. As a result, ceasefires often break down, and are used by parties to regroup, rearm, or achieve a tactical advantage.

All of these forces can prevent a resolution of conflicts and disputes. But as many mediators know, they can also be turned into opportunities for parties to change their positions and reach an accord.

Creating New Perspectives

Michel de Montaigne (1533–1592) understood what is necessary if we are to reach common ground. In his Essays, he argues we have no clear picture of the way things really are, but only of our impressions of the world and of one another. Montaigne believed much suffering can be avoided, and much good done, if only we admit our ignorance and examine people, and situations, more closely. He argued effective learning, and a life well-lived, comes by being present in the world. Montaigne looked to our shared habits and customs in order to find common ground. Similar commonality might be found in opening up the time frame to consider the long-term effects and consequences of conflicts and disputes.

The benefits of entering into the world in this way is inherent in the idea of perspective, which was first explored by Leon Battista Alberti’s (1404– 1472), in his book, De Pictura. Alberti explained how perspective in a work of art allows a viewer to see the world as if through a window, drawing them into the canvas.

Being present also is a core component of empathy, which, properly understood, is the capacity to identify with someone else and feel what they are feeling. Empathy comes from the German word Einfühlung, meaning ‘feeling into.’ To ‘feel into’ someone else’s position, it is essential to be present with them. Being present opens possibilities that applying the ‘lessons’ of the past does not. It is not an overstatement to say that being present offers us a way forward. Indeed, it even can be necessary to our survival.

Laurence Gonzalez, in his book Deep Survival, explores how being present often determines who will survive, and who will not. After interviewing scores of catastrophe survivors, he concluded that those who survived did not import past experiences into the crisis they were facing, but were present in the moment, allowing them to more clearly see what action was necessary. Those who looked to their past experiences often perished.

A 2014 Stanford study on walking suggests another reason why being present can play such an important role in our survival. The study concluded that peoples’ creativity increases sixty percent when walking. One explanation given for our enhanced creativity is that walking causes “cognitive fluctuations” that reflect the fractal patterns of nature, thus helping us in “identifying, navigating and remembering” those same patterns in the world.

There is reason to believe being present in the world in this way is what allows us to see it for what it actually is—a web of connections and dependencies. Heraclitus (sixth century BCE) wrote that we know only what such moments teach us, because “the only constant in life is change.” As a result, we only can know, and prosper, if we also change, adapting to the new worlds into which we enter.

Adapting to Changed Circumstances

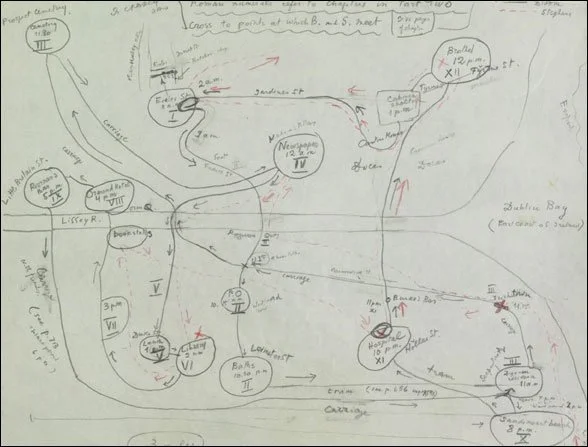

James Joyce (1882–1941) explored the same idea in Ulysses, his novel about an everyday walk taken by Leopold Bloom through the streets of Dublin. Bloom’s walk parallels the mythic journey recounted by Homer in The Odyssey, in which Odysseus survives a series of challenges and returns safely to his former home, Ithaca. But unlike Odysseus, whose trials were caused by the gods, Bloom’s survival requires only that he navigate the social, psychological, and mundane terrain of his personal life as he searches for connection and meaning. If Bloom is to overcome his challenges, he must, like Odysseus, be present, empathetic, and persevering. Both men display these characteristics in their respective narratives. As Joyce wrote in Ulysses, “Think you’re escaping and run into yourself. The longest way round is the shortest way home.”

But something else was required—Odysseus, and Bloom, had to change. In his book, Being and Time, Martin Heidegger (1889–1976) makes the case that when Odysseus arrived in Ithaca, he discovered his old world no longer existed. But he had also been changed by his journey, which made it possible for him to defeat his wife’s suitors and survive. As a result, Odysseus did not recover a former world, but brought a new one into existence.

The same can be said about Bloom, who also has to overcome a suitor, his wife Molly’s lover. Bloom’s victory is not achieved through combat, but by rejoining Molly in their marital bed, where he lies upside down with his head at her feet. Their head-to-toe tableau vivant reflects that while they are estranged, they still have a close bond. As he falls asleep, Bloom mumbles something mundane about breakfast the next morning, signaling that their marriage, while changed, has survived.

Joyce finishes Ulysses with a long soliloquy by Molly. As she lies in bed with her husband, she thinks of nature, musing “… I love flowers … God of heaven there’s nothing like nature the wild mountains then the sea and the waves rushing then the beautiful country with fields of oats and wheat … ” She is recalling how present, how connected, she feels in the natural world. She calls Bloom her “mountain flower.” Joyce’s description of her feelings is consistent with the findings of the Stanford study on walking.

Avoiding the Trap of Adhering to Settled Beliefs

Ulysses famously was written as a stream of consciousness, in which thought emerges from unknown, shared depths. Carl Jung describes the process in a letter to Joyce: “[y]our book as a whole has given me no end of trouble and I was brooding over it for about three years until I succeeded to put myself into it.” Jung affirms that understanding one another requires connection, and change. The past, and settled beliefs, are traps. But how can they be avoided?

The psychologist William Dember developed a theory of motivation that suggests an answer. Dember’s research explored what we choose to look at when faced with a range of choices. His experiments reveal that our attention is drawn to what is new or unfamiliar. Dember thought we did so out of curiosity. But why are we curious? One possibility is that novel stimuli represent opportunities and threats. An evolutionary response designed to seize the first and avoid the second makes sense. By such acts we prosper and protect ourselves.

Commercial and diplomatic negotiations also are an effort to prosper and protect by being present. For this reason, it makes sense to listen, and learn what is new. In our everyday personal and political lives this can be accomplished by creating ’third places,’ where people of different backgrounds can safely gather and hear what others have to say.

In the world of diplomacy, negotiations could take place proximate to where the conflict is occurring, enhancing the parties’ understanding of the actual harm on the ground. There is some precedent for such an approach, such as the negotiations to end the fighting in Darfur. But often concern for the safety of negotiators takes precedence. This is understandable, but deals a blow to the empathy that could be utilized in reaching an accord. In mediations, where there typically is not a ‘conflict zone,’ creating a safe place means something different— encouraging the parties, and their counsel, to be respectful and courteous, and to be active listeners and learners.

Overcoming the Challenge of Not Wanting to Know

Of course none of this is trivial. Many refuse to see the situation from another’s perspective. Eric Hoffer, the San Franciscan street philosopher, believed that “i[n] times of change, learners inherit the earth, while the learned find themselves beautifully equipped to deal with a world that no longer exists.” But he was also aware that “[f]ar more critical than what we know or what we don’t know is what we don’t want to know.” Negotiators and mediators must be prepared to guide parties away from their ‘preferred points’ based on past experience, to what might be called ‘placer points,’ where the present and future can be seen and realized.

Diplomats and mediators have many tools to do this, including discussing the challenges future generations will face if the negotiations fail; creating space for the parties to admit shortcomings, and even wrongdoing, in circumstances where the result will be seen as a compromise; encouraging apologies; finding ways to humanize and build connections between the parties by focusing on the suffering they have shared; managing shame, both as an impediment and as a catalyst to change; negotiating where harm has taken place; highlighting shared, foundational values; and even taking walks with those involved. But for any of these tools to work, negotiators and mediators must be prepared to use them without fear of their own failure.

Reconciliation begins by being a listener and learner, not a ‘knower.’ For this, the parties, and their respective counsel and advisors, must be present. Diplomats and mediators should look for opportunities to help parties leave the past behind, and find the new worlds ahead.

David L. Carden served as the first resident U.S. ambassador to the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. He is the author of Mapping ASEAN: Achieving Peace, Prosperity, and Sustainability in Southeast Asia and has written for Foreign Policy, Politico, the SAIS Review of International Affairs, the Guardian, the South China Morning Post, and Strategic Review, among others. He also is a mediator and serves on the Board of the Weinstein International Foundation, which promotes the use of mediation around the world.

Map of Leopold Bloom’s Journey in Ulysses (Vladimir Nabokov).