Why Does Crisis Stability Remain a Wild Goose Chase in South Asia?

By Safia Mansoor and Dr. Sufian Ullah

Why Does Crisis Stability Remain a Wild Goose Chase in South Asia?

Crisis in South Asia is not an anomaly but a recurring structural feature of a volatile regional environment; even small sparks can quickly ignite into strategic conflagrations between two nuclear rivals. Amid such enduring tensions, crisis stability becomes a strategic imperative. Crisis stability, an integral component of strategic stability, refers to a situation in which neither of the actors engaged in a political crisis fears the initiation and escalation of an armed clash, including preemptive strikes against nuclear assets. In other words, crisis stability entails confidence that a low-level conflict will not erupt into a major war.

Can nuclear deterrence be understood as a precursor to crisis stability between nuclear adversaries? Nuclear weapons contribute to a baseline deterrence effect, but crisis stability requires a force posture that not only deters, but also reassures a state’s leadership of the ability to prevent war without yielding or making concessions. The delicate balance between deterrence and reassurance represents the critical sweet spot in preserving strategic stability. In South Asia, however, this balance remains elusive due to doctrinal asymmetries, technological shifts, and institutional hurdles.

Crisis stability remains a difficult objective in South Asia due to the differing approaches of India and Pakistan: it is synonymous with a wild goose chase, often visible but never in reach, causing both states to toe the line bifurcating provocation and escalation. Recent military crises over the last decade—including India’s ‘surgical strikes’ in 2016, the February 2019 crisis, and, most recently, the ninety-six hour long May 2025 crisis—demonstrate how strategies focused on warfighting and compellence, instead of deterrence and crisis management, make crisis stability more elusive in South Asia.

Indo-Pak Doctrinal Disparities

Among the most defining features shaping the possibility of crisis stability between Pakistan and India are doctrinal disparities, which generate misperceptions about escalation control and undermine the foundation upon which crisis stability could otherwise rest. Since the Twin Peak Crisis, India has been pursuing space for “limited war” below the nuclear threshold as a function of its Cold Start Doctrine, which revolves around launching punitive strikes deep inside Pakistan and securing limited strategic objectives. In recent years, India’s shift from a ‘Proactive Operations Strategy’ to a ‘Dynamic Response Strategy’ (DRS) signifies a resort to multi-faceted or hybrid response options below the nuclear threshold to materialize conventional preemptive strikes against Pakistan. The core aspect of DRS is its focus on escalation dominance to retain control over the pace and intensity of a conflict rather than relying on solely retaliatory options.

Following India’s pursuit of limited war, Pakistan adopted a strategy designed to deny battlefield gains called ‘Full Spectrum Deterrence’ (FSD). FSD is grounded on credible minimum deterrence principle and addresses multiple levels of the threat spectrum including tactical concerns. Credible minimum deterrence relates to the ‘credibility’ of retaliatory capability, which implies both a survivable nuclear arsenal and practice of ‘minimalism’ signals restraint and disinterest in an arms race. Minimalism also entails Pakistan’s pursuit of a nuclear arsenal sufficient to meet the contextual demands of a particular strategic environment. Moreover, Quid Pro Quo Plus (QPQ+), the conventional corollary of FSD, reflects a proportionate and calibrated policy response intended to maintain ‘deterrence by denial’ while refraining from vertical escalation.

India's doctrinal thinking is reflected in claims of aerial precision during engagements in 2019 and 2025; Pakistan's can be observed in Operations Swift Retort and Banyan um Marsoos (demonstrating QPQ+ in action). On August 14, 2025, Pakistan announced the formation of Army Rocket Force Command, which will reportedly manage conventional missiles such as Fateh series. Separating conventional inventory from nuclear forces will further strengthen QPQ+ and in turn augment the conventional component of FSD. In summary, India’s doctrinal inclination seeks to make space for military action below nuclear threshold, while Pakistan’s doctrinal adjustment aims at restoring deterrence and preventing India from taking any such advantage. It demonstrates significant asymmetry: one side seeks to exploit an operational gap while other side commits to deny the use of that gap.

Counterforce Temptation

Secondly, the proclivity for counterforce strategies is a dangerous trend that begets crisis instability. In recent years, India’s nuclear posture denotes a growing doctrinal and technological drift toward counterforce capabilities. The dissent in the Indian strategic community over its No First Use (NFU) policy is becoming palpable, as reflected in the statements of former Commander-in-Chief of India's Strategic Forces Command Lt. Gen. BS Nagal, former Indian defense minister Manohar Parrikar, and incumbent defense minister Rajnath Singh. Former Indian national security advisor Shiv Shankar Menon talks about a “potential grey area” with respect to contemplating a preemptive strike following the mere threat of nuclear weapons use. India’s “counterforce temptations” arise from its “strategic paralysis” concerning Pakistan and the belief that strategic freedom of movement can be obtained only by undermining its adversary’s nuclear capabilities. To put simply, counterforce temptations imply shift to incorporate counterforce options whereas strategic paralysis refers to inability of India to act decisively due to fear of Pakistan’s tactical nuclear weapons. Technological acquisitions by the Indian military are in line with these doctrinal changes. Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD) systems, hypersonic weapons, space-based Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR), and missiles equipped with Multiple Independently Targetable Re-entry Vehicles (MIRVs) furnish the technological prowess to carry out counterforce strikes and reduce the perceived cost of a first strike. Development of Agni-V Intermediate Range Ballistic Missiles (IRBMs) equipped with conventional bunker buster capability is also a step in this direction. Space assets of India such as the Cartosat series improve ISR capabilities enabling a close watch on military installations, movements, and infrastructure along the eastern border, compressing decision-making timelines and increasing the likelihood of miscalculation during crises.

Enhanced ISR capabilities specifically endow India with an asymmetric advantage and sparks concerns related to the allure of a decapitation strike on Pakistan during a conflict scenario. After the successful test of Hypersonic Technology Demonstrator Vehicle (HSTDV) in 2020, India embarked on co-development of the Brahmos II, which will substantially reduce missile flight time between Pakistan and India. Hypersonic weapons would allow India to carry out preemptive, precision strikes against Pakistan while BMD systems promise absorption of a counter-strike, exacerbating an assumption of costless escalation. Consequently, the Observe, Orient, Decide, and Act (OODA) loop will shrink, making Pakistan’s threat assessment and response risky and difficult. The compressed OODA loop will inevitably constrict Pakistan’s ability to carry out a holistic situational assessment before delivering a response. OODA compression would amplify cognitive biases and misinterpretations of strategic signals, thereby heightening the chances of inadvertent escalation.

Lack of Crisis Management

Crisis management is a key tool to achieve and maintain crisis stability, absence of which often results in overreliance on international or third-party mediation. The third factor behind crisis instability in South Asia is a lack of institutionalized crisis management procedures such as de-escalation protocols, effective and operational hotlines, and bilateral strategic dialogues between Pakistan and India. Historically, third party mediation has proven useful for crisis mitigation. However, diplomatic interventions have failed to address the root causes of crisis and haven’t translated into Confidence Building Measures (CBMs). Hotlines exist between the two states, but they tend to remain inactive during crises because there are no well-delineated de-escalation protocols such as leader-to-leader hotline, institutionalized back-channel diplomacy etc.

Burgeoning Arms Race

The doctrinal shift in South Asia has catalyzed a regionally-destabilizing arms race between Pakistan and India that has been exacerbated by the influx of weapons from extra-regional actors. The Indo–Russian defense partnership is one such example: India imported 65 percent of its weaponry (worth $60 billion) from Russia in the last two decades including S-400 Air Defense Systems, Su-30MKIs fighters, T-72 tanks, AK-203 assault rifles, co-produced BrahMos cruise missiles, Talwar-class frigates, and Akula-class nuclear attack submarines. Israel, France, and the United States were also top arms suppliers to India during the last five years, responsible for nearly 55 percent of India’s weapon imports.

To counterbalance India, Pakistan has forged a strategic partnership with China. The most notable results of this strategic partnership are VT-4 Tanks, J-10CE fighters, co-developed JF-17 fighters, Type 054A/P frigates, LY-80N surface-to-air missiles, and jointly-developed Hangor-class attack submarines, of which a third has been recently launched in China. The infusion of technologically advanced military systems not only widens conventional imbalance but also complicates decision-making processes, affecting both sides’ perceptions regarding speed and initiative in a crisis.

Integration of Advanced Technology

Technological sophistication and advanced military systems are also eroding crisis stability as they amplify lethality and expand the number of operational domains. The May 2025 crisis exemplified how emerging technologies are transforming South Asian warfare. The four-day crisis involved drone duels, cyberattacks, and precision strikes backed by space-based ISR. With respect to India, key weaponry employed during Operation Sindoor included Rafale fighters embedded with SPECTRA electronic warfare systems, AESA radars, and Meteor beyond-visual-range missiles. India also used Brahmos cruise missiles and drones such as the Harop, Harpy, Nagastra-1, ASL, Warmate R, and Warmate 3. Pakistan’s response, Operation Bunyan um Marsoos, employed J-10C and JF-17 fighters, PL-15 missiles, and the Link-17 data link. Pakistan also deployed various drones including the Asisgaurd Songar UAV and the Yiha-III loitering munition. At the same time, Chinese ISR played a vital role for Pakistan’s air force.

A Path Forward

The cumulative impact of these developments is divergence from the predictability and restraint that are necessary for crisis stability. Enduring crisis stability in South Asia requires engaging in strategic dialogue to acknowledge each other’s vulnerabilities and identify a common framework as the foundation for strategic stability. Crisis stability requires not just military restraint, but also institutionalized dialogue, doctrinal transparency, and mutual recognition and clarity of red lines. Institutionalizing clear escalation thresholds would beget transparency during crisis whereas developing and integrating de-escalation protocols into routine diplomatic and military planning can help diffuse tensions. Without formal crisis management protocols, South Asia will remain trapped in the oscillations between escalation and near-miss crisis that threatens to spiral out of control.

Safia Mansoor is a Phd Scholar of International Relations at the School of Integrated Social Sciences at the University of Lahore. She received her MPhil in International Relations with gold medal from the Kinnaird College for Women. She has also served as Research Associate at the Maritime Centre of Excellence at the Pakistan Navy War College in Lahore. She has number of publications (Journal articles and short academic articles) published nationally and internationally. Her areas of interest includes Defense and Strategic studies, Emerging Military Technologies, South Asia, and the Asia-Pacific Region.

Dr. Sufian Ullah is a Senior Research Fellow at the Maritime Centre of Excellence at the Pakistan Navy War College in Lahore. He holds a PhD in Defence & Strategic Studies from Quaid-i-Azam University. He is a former visiting fellow at the Center for Non-Proliferation Studies and Sandia National Laboratories, and completed a CYG-CENESS Research Fellowship. He frequently writes on issues related to strategic stability in South Asia and emerging dynamics of sea-based nuclear deterrence in the region. As a Mentor for the UN Office for Disarmament Affairs (UNODA) Youth Leader Fund (YLF) Mentorship Program, he also guides and supports young leaders in advancing non-proliferation, arms control and disarmament efforts.

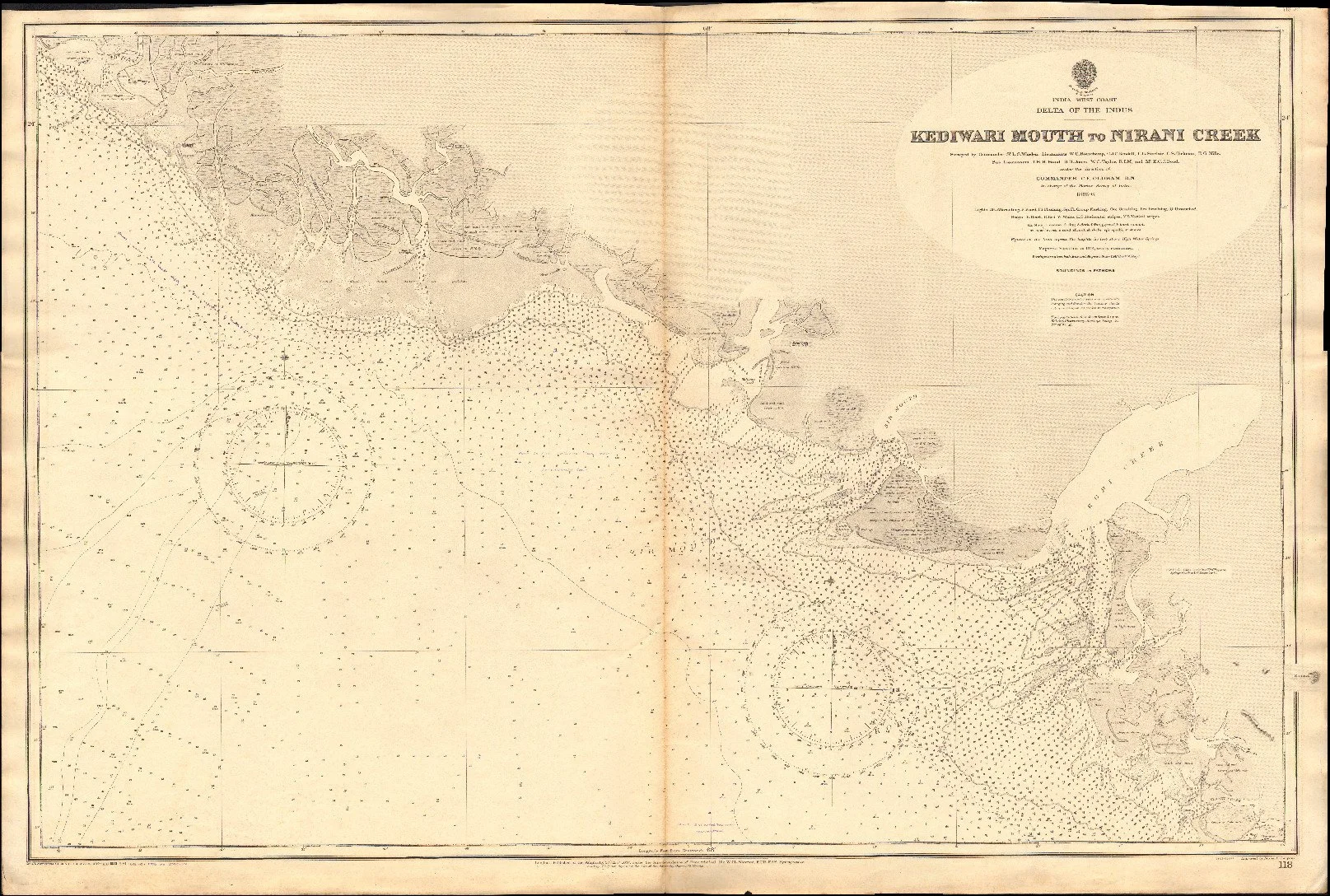

Portuguese map of the Indian Ocean, Africa and Arabia (Pedro and Jorge Reinel).

Licensed under CC0.